-

Market Cycles

Let’s start off this post with a question: What do forests and the stock market have in common?

They both tend to follow cycles.

Forests tend to follow a cycle: They start from a few seeds and some fertile soil. Over time, those seeds grow into a lush, green forest. The forest becomes too overgrown and begins to fill with dead wood that dries out. Eventually, something like a lightning strike, a campfire, or a carelessly discarded cigarette sparks a fire, and that fire ravages the forest. When the smoke clears, all that is left is a gray, ash-covered landscape. Time passes, and animals begin to return to the land. Some of those animals carry seeds, which fall into the soil, and with the help of the fertile, ash-filled soil, begin to grow into trees again.

So what does this have to do with the stock market?

The same thing (metaphorically) happens with the stock market.

The cycle starts when nobody wants to own stocks. Everyone are afraid that they’ll lose their entire investment, so they steer clear. A few investors start doing some research, and find a few stocks that they believe are cheaply priced and will grow tremendously over time, so they start buying. With time, others start to catch on, and more people buy in. As more and more people buy these stocks, the more the stocks increases in value, and the more money the stock owners make. These people then start to become renowned for their investment prowess, and word gets out how smart and rich they are. As word spreads, people copy their moves in hopes of achieving a similar result. Eventually, the price of the stocks get so high that people become fearful that everything is extremely overpriced (also known as a bubble). When this happens, less people buy stocks, and some even start selling. All of a sudden, something spooks the investors, such as bad news about the economy or rising interest rates, and the trickle of selling becomes a gusher. Stock prices fall like a rock, and money is lost as fast as it was made. Eventually, everyone has sold their stock, and horror stories of people losing everything run rampant. Nobody wants to own stock. But then, along comes a group of investors.

These market cycles have been present since financial markets began. Extreme examples of these include the Dutch Tulip Mania of 1634-37, during which, prices for individual tulip bulbs reached up to 10x the annual income of the average Dutch worker, and more recently, the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC).

Let’s use the GFC as an example. In the early 2000s, the stock market was recovering after being decimated by the end of a bubble in new internet companies. With time, people began buying stocks again, and the market began to rise. As the early 2000s became the mid 2000s, some people began to worry about the stock market being overpriced. However, prices continued to rise. Eventually, rising interest rates led to a rapid decline in the red-hot housing market, which then spread to the stock market. America’s financial industry faced massive losses and the threat of bankruptcy. Millions of people lost huge amounts of their money, and in many cases, their homes. There was a fear that gripped people ranging from the average joe to Wall Street titans that the global financial system would collapse. People couldn’t get rid of investments fast enough. But then, eventually the selling slowed, and investors began buying again. The buying continued, and the stock market went on to post one of its best decades of all time in the 10 years after the GFC.

Not all cycles are created equal. Sometimes, the economy is managed by the Federal Reserve, which acts like a forest crew doing controlled burns to reduce the available fuel for forest fires, and the swing between selling and buying is fairly gentle. Other times, the market is allowed to run uncontrolled, and the pendulum swings much farther in each direction.

While it is impossible to predict the exact timing of these cycles, it is possible to get a rough sense of where you are at in the cycle by paying attention to things like people’s attitudes about the market. We will get into this in more detail in another post, but for now, I want to convey that these cycles exist, and will likely continue to exist for as long as we have financial markets.

-

The Power of Compounding

Picture this: you pack a snowball and plop it down onto the snowy ground. You pack a bit more snow onto it, and then roll it down the hill in front of you. What happens as it rolls down? It gathers more snow, and it grows. The farther it rolls, the more snow it picks up. By the time it reaches the bottom, your once-little snowball is gigantic.

What if I told you that it works the same way with money?

The financial term for this effect is compounding. Compounding refers to the cycle of earning income from an investment, and then putting that money back into an investment so that it generates more income. This income is then reinvested again, which generates more income, and so on and so forth.

“That sounds boring. What’s the point of making money if you don’t get to spend it?”

Let’s say that you inherit $10,000. You consider three options:

- Option #1: spend the $10,000 right away

- Option #2: buy $10,000 worth of a stock and spend the dividends from it

- Option #3: buy $10,000 worth of a stock and reinvest the dividends from it until you retire

Let’s see how each of these scenarios plays out.

Option 1: you spend the $10,000, and you have the thing that you spent the money on, but no more money or income from it.

Option 2: every year, you get $1,000 worth of dividends from your stock, which you then spend. After 40 years, you are still making $1,000/year without having to work for it, plus you still have your original $10,000.

Option 3: That stock pays a 10% dividend, so by the end of the year, you have $1,000 cash from the dividends. You then take that $1,000 and buy more stock. The next year, you get 10% of $11,000 (original $10,000 + $1,000 from dividends), which is $1,100. You then take that $1,100 and buy even more stock. Now you get $1,210, which you then roll back into more stock. You’re making a little bit of money, but after three years, you’re only making $210 more than if you had spent the dividends on something fun and kept collecting 10% of $10,000. Why not just spend it?

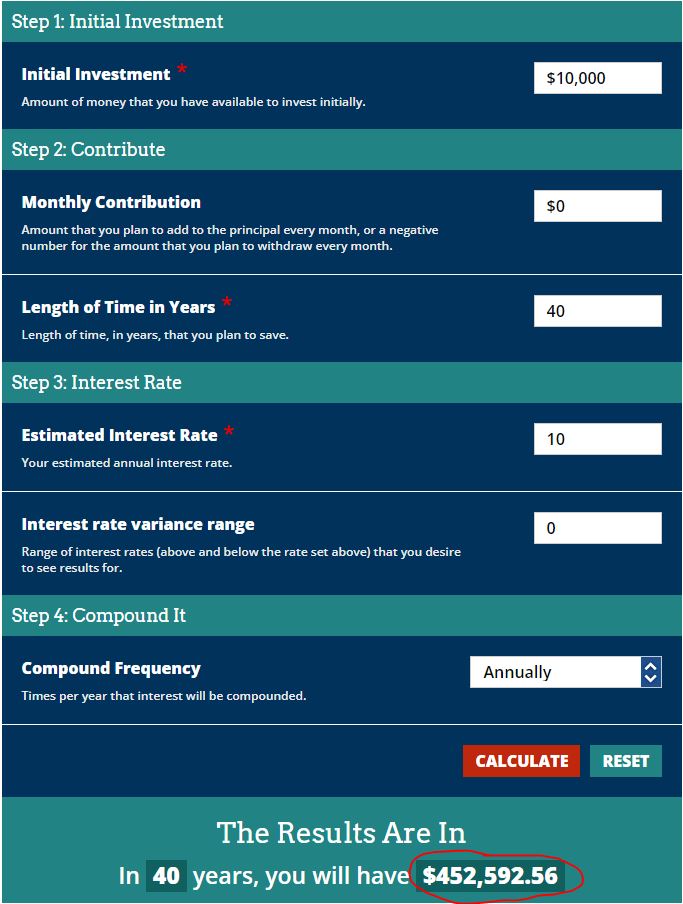

Let’s take a look at what happens if you do the same thing for 40 years. You can figure this out this calculator.

As you can see, if you don’t contribute any other money besides the initial $10,000, earn 10% every year, and let the money grow for 40 years, that $10,000 ends up being worth $452,592.56! By now, you are bringing in $45,259.25 each year in income from your dividends.

These numbers only goes up if you add more money to your investments as well. For instance, if you start adding $500 per month and leave all of the other numbers the same, after 40 years, you end up with an investment worth $3,108,147.89 and $310,814.79 of dividend income!

These numbers don’t factor in taxes, which decrease the end amounts. However, you can minimize the effects of taxes by using retirement accounts like your 401k/403b and your IRA.

-

Tax Deductions

So what is a tax write-off? I’ll let Johnny Rose do some of the heavy lifting on this one.

As Johnny said, tax write-offs (aka tax deductions) are expenses that are used to reduce your taxable income. He mentioned business expenses specifically, but there are also many personal tax write-offs as well. Some of the most popular personal deductions include:

Above The Line Deductions

- Retirement Account contributions (IRA/401k/403b)

- Health Savings Account contributions (HSA)

- Student Loan interest

Below The Line Deductions

- Mortgage interest

- State and local taxes

- Charitable donations

- Medical expenses that exceed 7.5% of your income

- Student Loan interest

- Education expenses

Above the line deductions are deductions that can be taken in addition to the standard deduction. Below the line deductions cannot be taken in addition to the standard deduction – you must choose between below the line deductions or the standard deduction.

Standard Deduction

The IRS offers something called the standard deduction. The standard deduction is a predetermined amount that tax payers are allowed to use on their taxes instead of itemizing (making a list of) their deductions. Even if your deductions are less than the standard deduction, you can apply the standard deduction to your taxes and shave that amount off of your taxable income. It changes from year to year because it is tied to inflation, so it is important to use the the correct year’s standard deduction. For instance, from 2021 to 2022, the standard deduction rose from $12,550 to $12,950 (for those filing single) and $25,100 to $25,900 (for those filing jointly).

So what does it mean to reduce your taxable income?

As we remember from the post about income tax brackets, in the US, you pay more in taxes as your income increases. Tax deductions allow you to decrease the amount of income that you owe taxes on so that you end up with a lower tax bill. For example, if your income in 2022 is $60,000 and you have use the standard deduction, your taxable income falls by $12,950 to $47,050. This means that when you are looking at the income tax bracket, you would use $47,050 instead of $60,000!

So should I use the standard deduction or itemize?

The rule of thumb that is typically used to determine the answer to this question is to look figure out a ballpark total of your deductions. If that total is greater than the standard deduction, itemizing will likely be your best bet, depending on what expenses you have records of and how long it will take you to itemize everything.

-

Tax Brackets

What’s exactly is an Income Tax Bracket?

In the United States, we use a system that charges a different tax rate depending on your income. As your income increases, so does your tax rate. These different rates are called tax brackets.

One of the common misconceptions is that if your income is high enough to push you into a higher tax bracket, you owe a higher tax rate on every single dollar that you have made that year. However, that isn’t how our system works. Instead, you only pay that higher rate for each additional dollar that you earn above a certain amount. The way to you find out how much you owe based on your income is to find your current income on the IRS tax bracket chart, and use the income and tax rates in the chart.

For example, if you get bumped up from the 12% to the 22% tax bracket because you are making $60,000, you don’t owe $13,200 in taxes (60,000*0.22).

Single tax rates 2022 AVE/IRS How to do it the old-fashioned way

(you can skip to the next section if you care less about the journey than the destination)

To find out how much you owe in income taxes, you add:

- 10% on any income up to $14,650 (a maximum of $1,465, which is found by 14,650*0.1)

- 12% on any income between $14,650 and $55,900 (a maximum of $4,950 which you find by subtracting the $14,650 that you already paid 10% taxes on from the $55,900 upper limit to find the amount that you haven’t paid taxes on yet, and then multiplying that 41,250 by the 12% tax rate to get 4,950)

- 22% on any income between $55,900 and $89,050 (you subtract 55,900 from your 60,000 income and get 4,100. You then multiply that 4,100 by 22% to get 902 because that is the amount of your income that is above 55,900 and that you haven’t paid taxes on yet).

With all of this information, you can then add up the 1,465 from the first bracket, 4,950 from the second bracket, and the 902 from the third bracket to get $7,317 that you owe in taxes.

How to do it the easy way

As you can see from the chart (which I added in a second time so that you don’t have to scroll back and forth), the IRS does the math for you on how much you owe for the lower tax brackets, so you can use the formula provided on the chart. You find your tax bracket, subtract the lower limit of your bracket from your income, (60,000 salary – 55,900 bracket limit) and then multiply that amount by the tax rate for that bracket (22% in this case) to get $902. You then add the stated total from the lower brackets (in this case, $6,415) and add it to the $902 and get your income tax total of $7,317. As you can see, this is much lower than if you had to pay 22% of every dollar that you made!

Single tax rates 2022 AVE/IRS How to do it the easiest way

Many websites offer calculators for finding your income tax bill. Just be careful about which year they are designed for because income tax brackets are constantly changing!

-

401Ks, 403Bs, and IRAs

I keep hearing about these. What are they???

In short, they’re all types of retirement accounts. They are designed to encourage you to save up your money for retirement by allowing you to save money on your taxes, depending on which account type you choose and how much money you contribute to them. They also discourage you from taking money out of them before you retire by imposing taxes and penalties if you do so (except for under specific circumstances).

401Ks and 403Bs

401Ks and 403Bs both fall into the category employer-sponsored retirement plans. All this really means is that they are linked to your job, and with that come certain perks and responsibilities.

Depending on your employer, you might get your contributions matched up to a certain amount (meaning that for every X # of dollars or % of your salary that you contribute, your employer will contribute a certain amount of money to your account as well. Different employers have different rules for matching, so that can potentially be one of the things to look at when you’re considering a job.

Because your account is linked to your employer, if you take a job somewhere else, you will have to get a new account set up with your new employer. Each employer has a specific list of financial companies that they work with for their retirement program; sometimes that list is long, sometimes it’s just one company.

For more about employer-sponsored plans, click here.

What’s the difference between a 401K and a 403B??

The main difference is that 401Ks are for employees of privately owned, for-profit companies, whereas 403Bs are for employees of non-profit organizations and governments. Some 401Ks also offer investment options that 403Bs (which are typically limited to mutual funds) don’t, such as individual stocks and ETFs.

So what’s an IRA?

IRA stands for Individual Retirement Account. In contrast to 401Ks and 403Bs, IRAs don’t go through your employer; it’s all up to you. As long as you have earned income (wages, salaries, bonuses, commissions, tips, or earnings from self-employment), you can open and contribute to an IRA. When you change jobs, you don’t have to make any changes to your IRA.

For more about IRAs, click here.

Roth vs Traditional

There are two types of IRAs that you’ll often hear about: a Roth IRA and a Traditional IRA. Roth IRAs allow you to taxes on your contributions and then withdrawals (taking money out of your IRA) is tax free. Traditional IRAs involve the opposite: you can deduct contributions from your income taxes when you put the money into your IRA, but you pay income taxes on it when you withdraw it.

Some employers offer Roth 401Ks and Roth 403Bs as well, but it varies from employer to employer.

So what’s the difference between an IRA and 401K/403B?

The main differences between 403Bs/401Ks and IRAs are:

- Contribution Limits: as of 2022, 401Ks and 403Bs allow you to contribute up to $20,500 per year ($27,000 if you’re over the age of 50). IRAs are limited to $6,000 per year ($7,000 if over 50). *Employer matching does not count towards contributions limits*

- Loans: Many 401Ks and 403Bs offer the option to take a loan from your account and as long as you pay the loan back, you can access that money without having to pay the penalties and fees that are usually a result of early withdrawals. IRAs do not offer loans.

- Employer sponsored vs individual: When you change jobs, you have to get your 401K or 403B switched over to your new job . With an IRA, you don’t have to make any changes when you get a new job.

- Income limits: IRAs have certain limits on the amount that you can contribute(Roth)/deduct from your taxes (traditional) based on your income. For Roth IRAs, anyone with an annual income of $125,000 (single) or $198,000 (married filing jointly) can contribute the full amount. For more info about these income limits, click here.

-

Mutual Funds, ETFs, and Index Funds

So you understand what stocks and bonds are… for the most part.

That’s okay. It’s going to take a few tries to get that “Oh! That makes sense!” moment. Stick with it, and let’s add on to things a little bit.

A fund is a pool of money that is used to invest in different things. It can be a group of friends that each chip in a few hundred dollars to buy stocks together, or a group of investment companies that gathers up billions of dollars to invest in everything under the sun.

The Four Fund Families

There are four main types of funds that people often talk about – mutual funds, exchange traded funds (ETFs), index funds, and hedge funds. For this post, we’re going to focus on mutual funds, ETFs, and index funds. We’ll talk about hedge funds later.

One thing that all four fund types have in common is that they seek to reduce the risk of losses to their investors through diversification. Simply put, diversification means that instead of putting all of your eggs in one basket, you spread them into many baskets. If, for instance, you put all of your money into one company’s stock, you can lose everything if that company does poorly or goes under. However, if you spread your money out into many different companies, it lessens the impact of one company’s performance.

Mutual funds

Investopedia.com defines a mutual fund as “a type of financial vehicle made up of a pool of money collected from many investors to invest in securities like stocks, bonds, money market instruments, and other assets. Mutual funds are operated by professional money managers, who allocate the fund’s assets and attempt to produce capital gains or income for the fund’s investors. A mutual fund’s portfolio is structured and maintained to match the investment objectives stated in its prospectus.”

In English? A mutual fund is a pool of money that is gathered up and managed by a professional manager in return for a fee. Depending on the mutual fund type and its stated goals, it may invest in stocks, bonds, or other types of things with the goal of making money for its investors. You can find out more about the fund by reading its prospectus.

Mutual fund shares are generally bought or sold at the end of each trading day and use the Net Asset Value (NAV, which is value of the fund’s investments divided by the number of outstanding shares) to determine trade prices.

*For more on Mutual Funds, check out investopedia.com.*

ETFs

An ETF is fairly similar to a mutual fund in that both types of fund allow investors to pool money together to purchase investments. The main difference is that unlike mutual funds, ETFs can be traded on a stock exchange, meaning that they can be bought and sold at any point during normal trading hours, and their prices can fluctuate. ETFs also typically have lower fees than mutual funds.

*For more on, ETFs check out investopedia.com.*

Index Funds

An index fund is a type of mutual fund or ETF that is designed to track the components of a financial index, which is a hypothetical group of investments that is based on a specific set of rules and used to track the movements of larger sectors of the economy. Well-known examples of indices include the S&P 500, which is made up of 500 of the largest publicly-traded US companies, or the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA/The Dow). Index funds follow the specific set of rules that are laid out in the construction of the index, so instead of a manager who is trying to find the best investments, the fund is constructed according to those rules. Because of this, the fees for index funds are typically much lower than funds that have an active manager running them.

*For more on, Index Funds check out investopedia.com*

-

Stocks and Bonds

Why does this matter?

For the average investor, stocks and bonds are the main investments that are easily accessible and common. Understanding stocks and bonds alone will not make you wealthy, but understanding them will help, and failing to understand them will create an Everest-size speed bump in your financial journey.

What is a stock?

Stock is defined by investopedia.com as “a security that represents the ownership of a fraction of a corporation.”

In non-dictionary English, this roughly translates to “owning stock means that you own part of a company.”

*For more on Stock, check out investopedia.com.*

What is a bond?

A bond is defined by investopedia.com as “a fixed income instrument that represents a loan made by an investor to a borrower (typically corporate or governmental).”

In essence, a bond is a loan. When you buy a bond, you are loaning money to the company/government, and in exchange, they are agreeing to pay you back by a certain date, as well as pay you interest.

For more on Bonds, check out investopedia.com.*

What does this look like in real life?

Stocks and bonds are both a way for companies to raise money. For instance, let’s pretend that your son starts a landscaping company. He starts off with your old push mower and mows a few lawns on your street. Over time, word spreads that he’s doing an amazing job, and the business grows.

One day, he comes to you and explains that he wants $25,000 to buy a truck, trailer, and bigger mower. The new equipment will allow him to make an extra $50,000 a year, but he doesn’t have $25,000. Fortunately, you have $25,000 that you’re willing to offer him. You have two options that you offer him:

-Option A: You can loan him $25,000, and he will have to pay it back within two years, plus pay you 5% interest. (Buying bonds)

OR

-Option B: You can offer him $25,000 to buy 10% of his company. (Buying stock)

So what does that mean for me as an investor?

If you choose Option A and give him the loan, you make money from the 5% interest that he’s paying you. You get that 5% interest per year regardless of whether his business becomes a huge success or just barely scrapes by, so you know exactly what you’re going to end up making. After two years, the loan matures, and assuming that his business didn’t go bankrupt, you end up with your original $25,000 (which is called the principal) back, plus $2,500 of interest ($25,000 loan x 5% interest x 2 years).

If you choose Option B and buy part of his company, your return depends on how the business fares. If the business flops, your investment will become worth less than $25,000, and it could become worthless if the business goes bankrupt. If the business takes off, the business will be more valuable than when you bought it, and your return will be 10% of however much the value increased. This does not put extra cash into your pocket until you sell your portion of the business, but if the business does well, there is no limit to how much you can potentially make.

Another way that you can make money is if your son decides to pay the owners of the company from the profits that are made. For instance, let’s say that the business ends up making $75,000 with the new equipment. Your son can decide to take $25,000 of the profits and pay the owners of the company (you and your son). This is called a dividend. Because you own 10% of the business, you would get 10% of the $25,000 being paid out ($2,500). Dividends can be paid as often as desired by the Board of Directors of the company, or not at all.

The path that best suits you depends on your financial needs and how you think the business will fare. Buying stock offers much greater potential reward, but is riskier because you’ll lose money if the company doesn’t do well. Buying bonds offers lower risk and lower potential reward because no matter how the company fares, unless it goes bankrupt, you get the principal amount plus the interest.

Stocks and bonds, along with other investments like ETFs and mutual funds through a brokerage company, which is a financial company that acts as the middle man for buying, selling, and holding onto your investments.

-

What is Investing?

First off, what is an asset? An asset is something can be used to generate income. Assets can take on many different forms, such as stocks, bonds, real estate, or other things.

Investing is when you trade your money for assets. These assets are supposed to (but don’t always) generate more income for you. When this happens, you can think of it as your money working for you. For instance, if you get a 10% return on a $1,000 investment, you have made $100 without having to do anything other than invest your money. If you earn $20/hour, it would have taken you 5 hours of work to earn that $100. This allows you the option of either working those 5 hours and ending up with $200, or taking those 5 hours off and still making $100. This may not seem super exciting, but if you stick with it for a while, continually invest in quality assets, and keep your investment money invested, you can grow your investments into an income producing juggernaut.

When saving for retirement and investing your money, you can think of your savings like your farm. After all, in both cases, you’re trying to build something that will provide the things that you need to survive and thrive. Let’s say that you have 40 years to build up a farm, and after that, you can only live off of what your farm provides for you.

Scenario 1: you think to yourself that 40 years is plenty of time to build a farm. You procrastinate a bit and do other things for 20 years. Finally, you realize that you had better get going on your farm. You start by buying a few chickens and a rooster, and a bull and a cow. You care for the animals a bit, and get some eggs and milk, but you get tired of them after a while, and you make yourself a chicken dinner here and a steak dinner there. As you eat your chickens, you get less eggs, so you become hungrier and you eat more chickens as a result of it. All of a sudden, it has been 40 years, and are devastated because you realize that you have nothing – you ate your chickens and cow, which were your only source of food, and while the dinners were delicious, you no longer get any milk or eggs.

Scenario 2: you think about it a little bit and realize that if you get started early, 40 years is plenty of time to build a huge farm that will take care of you and your family. Just like in scenario 1, you start by buying a few chickens and a rooster, and a bull and a cow. You realize that you can have the animals reproduce and grow your farm substantially by doing so. You get a ton of eggs and milk, and you trade some to your neighbor for some pigs and some fruit. You eat the fruit and plant the seeds from it, and as time goes on, those fruit seeds become an orchard. Eventually, your 40 years are up, but you aren’t at all bothered because you have a farm that provides more than you’ll ever need. You go outside every morning and get eggs, milk, and fruit. One of your chickens becomes dinner, but your other chickens have 5 chicks that hatched today, so you get to have your farm and eat it too.

In the beginning, you have to make do with what you have and be patient. However, if you are patient and let your farm grow, with time, it will begin to sustain itself and both grow larger and provide for you.

In this series, we’ll explore some of the common terms and concepts of investing and how to get started on building your farm.

-

Bored Man Gets Paid

Kawhi Leonard going for a ball in 2019. Steve Russell/Toronto Star If you’re not a basketball fan, you probably aren’t all that familiar with Kawhi Leonard. Despite being one of the top players in the NBA and the owner of a slew of accomplishments such as championships, Finals MVPs, All-star selections, and awards, Leonard is not a household name. He has, however, been able to cash in, landing a 4-year, $176.3 million max contract with the LA Clippers in 2021.

One of biggest reasons for his success? His love for the grind.

After the Toronto Raptors (led by Leonard) toppled Golden State in the 2019 NBA finals, people started talking about Leonard. One of the things that was dredged up and quickly adopted by many was Leonard’s old motto: The board man gets paid.

Getting rebounds is neither fun nor sexy. It requires a player to be physical and take a beating, and in return, you get very little recognition. Nobody dreams of getting a hard-fought rebound in the dying seconds of a tied-up Game 7 and passing it to their teammate. However, Leonard recognized the importance of getting rebounds and was able to leverage that into a spot in NBA history. Getting rebounds helps keep the ball in your team’s hands, and out of your opponent’s. This in turn gives your team more opportunities to score, and as John Madden so famously said, “Usually the team that scores the most points wins the game.”

Wow! Very cool!!! Some basketball player likes getting rebounds. What in the hell does that have to do with me?

The mentality of the grind will help you in virtually everything you will do in life. Fitness, finances, your career, your relationships – you name it. The ability to focus on doing the boring, nitty-gritty things in life really well will bring you tremendous successes, and with enough time and effort, the bored man gets paid.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.